Jack Brindley opened Pavilion Pavilion in Glasgow in 2019. Both a studio for his own practice & a gallery, it’s a place where the territory between & surrounding contemporary art & objects of use is explored.

What’s the view from Pavilion Pavilion’s window?

We look out onto St Andrew’s Street in Glasgow’s Merchant City and to student halls in what used to be the Sheriff’s office.

What was the impetus to opening Pavilion Pavilion in 2019?

It was to give shape to an aspect of my artistic practice that was increasingly leaning more heavily into the world of design. Working under the alias of Pavilion Pavilion gave me sort of licence to make things which otherwise would have been perhaps more of a mental contort within my art practice. I wanted the making and use of an object to lead over the conceptual. A lot of the inspiration comes from architects, such as the Italian architect Carlo Scarpa (1906 – 1978) who have a Gestamakunstwerk (total artwork) approach, designing everything down to the finest detail in a building. Glasgow, like many contemporary cities is in flux, there is a huge amount of development and the usage of spaces is often quite temporary. I wanted to take the model of a Pavilion as a way to explore what happens in the periphery when a city is being re-imagined.

Photograph by Kim Zwarts

And the word pavilion, it puts me in mind of cricket pavilions or more interestingly, Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion of 1929. So it suggests a sense of independence – a stand-alone structure which can toy with the fanciful or even the radical. Is this how you see Pavilion Pavilion?

Well yes, exactly that. Initially I was thinking more along the lines of pavilions made for international fairs; often ambitious, temporary and provocative structures that seem to sit in an idealised world, as opposed to the pragmatic and practical, everyday real world of architecture. I wanted to find a space for design and art that was about a ‘what if?’ scenario. I wanted the potential to take risks. It’s a clear facet of contemporary art but there is a speed at which an object becomes a ‘thing’ in design that often stops it in its tracks. Pavilion Pavilion is also a curatorial project where I invite artists working in design to present an exhibition in the front bit of my studio. So in a very literal sense, it means to house a project or an idea.

As to your own practice as an artist, designer, maker and a curator, it seems you enjoy exploring the boundaries & meeting points between these disciplines? How do you describe these explorations?

Ah yes, well I guess I’ve never really thought about explaining them. In 2009 I started up a curatorial project called Open File with curator Tim Dixon, around the same time that I started a Masters at the Royal College of Art in Painting. Looking back, the majority of the shows we made were performance and video-led which I suppose gave me room to engage with practices which seemed far away from my studio practice. I’ve also produced work under the alias Clay Arlington, as a collaboration with the artist Lucas Price. I guess that Pavilion Pavilion is yet another way to explore authorship and to free up a bit of space: my own identity as an artist taking a back seat. I often think of Donald Judd’s title Specific Objects for his sculptures, which seem to perfectly sum up his ability to jump between art to design, for Judd sometimes that line between disciplines seems to dissolve completely.

I like your series ‘Exercises in Shelving” – can you talk a little about your design process?

A lot of my work is fairly process based, there are clear styles and ideas that I am interested in communicating but actually it is about making, especially with this series of shelves.

You had hoped to work with the artist Ryan Gander for this year’s Glasgow International. Can you talk a little about the project?

The show will now take place in April 2021 to coincide with the new dates for Glasgow International. The work by Ryan Gander is clear and witty, such is the way with majority of his work. Essentially he has made a replica of the architect Erno Goldfinger’s pipe as a functioning door handle. The architect was famous for his Brutalist architecture, especially his Trellick and Balfron towers in London. (The project has a personal connection too, as I would often stare at the Trellick Tower from my bedroom window, in the house I grew up in with an architect father). Goldfinger was celebrated and criticised in his time but like many Brutalist architects, he was ousted with the arrival of the Post-Modern style and tower blocks became synonymous with low-cost, ill-conceived design. Ryan’s work hints at Magritte’s The Treachery of Images painting, ‘Ceci n’est pas une pipe’ which calls into question the reality of objects and language.

Photograph Peter Trulock

What makes you tick?

So many things! The most exciting is also perhaps most difficult to describe. I love that piercing moment of clarity when an ill-defined piece of logic seems to click into place, that indescribable feeling you get through seeing an excellent artwork, reading an agile combination of words, even stumbling across a weird combination of objects on the street. Somehow there’s a huge amount of information packaged so perfectly, that it couldn’t be presented in any other way. Usually for me this happens mid-morning after that strong coffee. Ha!

Who’s your favourite writer, architect, artist or designer?

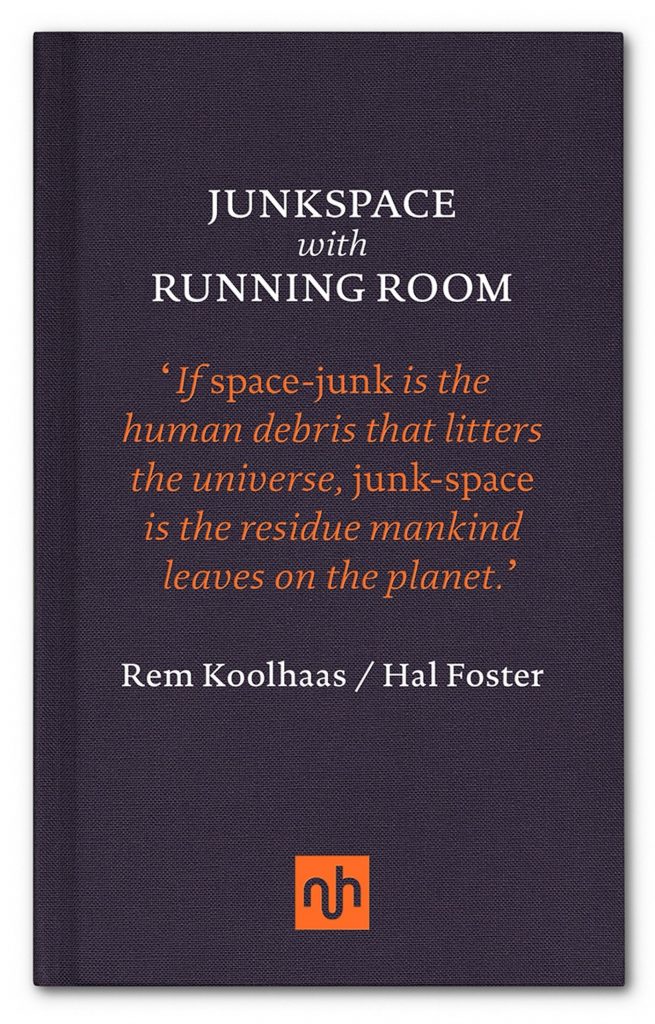

What an impossible question! Although I’ve always been amazed how the Dutch creative & architect, Rem Koolhaas has moved between all three of these roles pretty seamlessly. His writing in Junkspace is pretty excellent.

Has this period of confinement led you to think differently, to re-assess your ideas?

I have decided to focus on lighting and stained glass for a little while to try and pick away at the possibility of coloured glass becoming more architectural and brutal instead of stopping short at the decorative. But yes, I think lockdown has reminded me that it’s supposed to be fun, there is always a danger in turning art into something too task-based or market-driven. I’ve been following the Black LIves Matter protests closely and as a side note I am particularly fascinated in the removal of statues and monuments. I plan to spend the rest of the summer in the studio welding together an ever changeable structure, as a way to explore how we can bring about a new monumentality that is not politically specific yet built on awareness and openness. These should be visible from the street, (20 St Andrews Street, Glasgow) so come and have a look.

What next?

I have produced a huge stained glass commission for David Dale Gallery in Glasgow, which will be a permanent feature in their building. I am also hoping to shore up exhibitions at Pavilion Pavilion, once we are clearer the on-going impact of Covid-19. I am looking forward to working with Al Fresco 2000, a pair of French painters producing wearable paintings; the artist Richard Hards, who makes provocative interventions and Curbar Cycling, a cycling apparel company set up by curator David Mcleavey and artist James Clarkson.

David Dale Gallery, Glasgow