Suzanne Ewing reflects on The Burrell Collection, its architecture & its location within the green stretch of Glasgow’s Pollok Park.

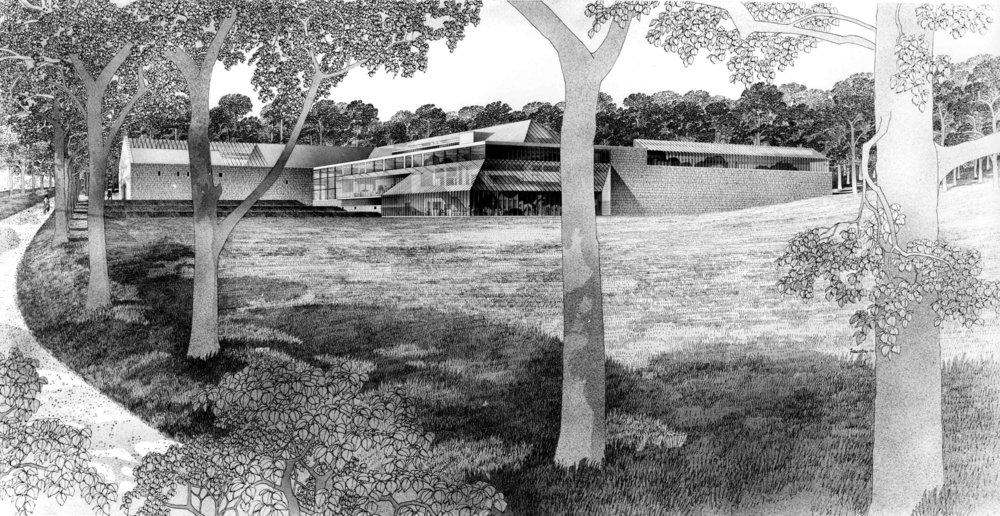

Brit Andresen, Barry Gasson and John Meunier designed The Burrell Collection in Glasgow to shelter an eclectic collection of valued objects but also to be an archetypical sheltering place. In a description accompanying the 1972 second stage competition entry, the architects wrote, “The building touches the trees, its glazed north wall allowing the woodland space and the space in the museum to become one. We thought of the walk along this edge as ‘a walk in the woods’.”[i] Andresen, after a subsequent career in architectural practice and education in Queensland, Australia, reflected on the relief that the building’s landscape-immersed edge offered to returning visitors.[ii]

Ship-owner Sir William Burrell (1861-1958) gifted his vast collection of over 8000 objects to Glasgow in 1944, with the condition that they would be housed away from the poor air quality of the day. No sites were immediately identified. In 1966 Pollok Park, 361 acres of parkland to the south west of Glasgow, was bequeathed to the city. This led to the announcement of a competition to design & build a new museum. A two-stage architectural design competition ran from 1971-72, with design and construction taking place from 1976. The building opened in 1983.

Shelter in place has been a recurring Covid-19 command. It seems to be most prevalent in the US context, rather than the confinement, lockdown, or stay at home messages of more deeply urbanised Europe. The phrase suggests intimate conditions within landscapes, harbouring from storms, natural disasters, feeling safe whatever the weather.

“The natural imagination is the infrastructure of architectural experience.’ [iv] wrote Colin St John Wilson in Architectural Reflections, 1992: 18

In the collective pause triggered by a global pandemic, I have been reflecting on the architectural places and experiences that might be a touchstone for, or offer inspiring examples of, sheltering in place. I write from our Edinburgh design studio which I have spent much more time in recently. Usually I am away in the peripatetic sites of education and research. It is a sheltering space, the timber-lined soffit sloping towards the long window’s northern horizon: the clerestory structuring shafts of afternoon light onto a more cluttered desk landscape of the projected, and potential worlds within worlds of digital hardware, office files, material samples, plants and an accumulating collection of drawing tools and boards.

The moment of initial Covid-19 crisis is passing, yet our infrastructures of experience are still in a state of desiccation. We are longing for places of relief that resonate with natural imagination, that nourish and enrich mundane and fleeting everyday routines. Hills, moors, beaches, tides, woods, gardens, magnificent halls. Stillness, seasons, window-seats, slowness, being grounded yet also uplifted. There’s little room for the Instagram-touched up architectural gesturing that has crowded visual media and discourse over the past few decades. On re-reading the opening chapter of Wilson’s Architectural Reflections, I was stopped short by the Le Corbusier quotation, ‘But suddenly you touch my heart.’[i] When and how did we get so distracted from this essence of architectural ambition and achievement?

The Burrell’s architects were influenced by Wilson’s philosophy and practice, which continued to explicitly thread through the built works of Andresen O’Gorman’s subsequent 25 years of making buildings in a very different climate and culture. They articulate an approach to projects underpinned by an ’empathetic imagination’ which they observed can be suppressed by the more dominant ‘inventive imagination’. They cite Wilson’s understanding of imagination as a ‘bridge’ in the process of synthesising factors of inhabitation, construction, environment and culture in making architecture and are drawn to “the intimacy of inhabiting a wild place that might also be paradise.”[ii]

“A building acquires a poetic dimension where the architecture engages the appetite of the senses and enters the imagination. And assertiveness in architecture may present itself more as an invitation than a command, where some choice and interaction are offered, where there is a fit with the needs of everyday life and where the poetic is experienced in the act of use.” [iii]

This is architecture that is less about vying for attention, more about attending to detail, unfolding modestly over time through gently oriented daylit paths, the glancing of a hand on a cool polished concrete column or grainy stone, the patterns of interwoven shadows that seem to confidently configure the rhythm and arrangement of objects on plinths, the hushed hues of the stair treads leading to the mezzanines to study paintings, and the degrees of warmth that differentiate the northern and southern interiors of the building. I have visited the Burrell several times since it opened in 1983. I have walked through the strong stone courtyards and along the wooded perimeter, meandered into different darkened rooms and on each occasion leaned on the red sandstone ledge in the spatial cascade that encompasses the sunny café fronting the grassy openness of Pollok Park. It is these qualities of invited experience, shared by many, that were defended during the recent redevelopment proposal debates, addressing a number of curatorial, visitor, fabric and environmental performance upgrades of a 40 year old building, yet aspiring to retain its original essence.[iv]

At the moment the Burrell Collection Museum is in a phase/pause of alteration, and will not be open again until at least 2021. It is still possible to go for a walk in those woods with Helmut Jacoby’s 1974 two-point perspective design development drawing: an exquisite exercise in empathetic imagination. Intricate jewel like leaves fill the sky and are echoed in the texture of the tapestry and accumulated vessels inside. The concrete columns’ junctions with the pitched timber roof beams seem to be mimicked by swaying trunks and branches; the strongly geometric shadows from the rooflight mullions and Chinese vases on the highly reflective floor dematerialise any earthy ground. The carefully crafted and cropped projection of the drawing is dramatized through tone and line, suggesting that the treasures and people being sheltered here have truly settled into place, as this place has now entered deeply into our imagination. [1122]

[1] The drawing is reproduced in ‘Andresen Gasson Meunier, Burrell Museum’ (1970-72) UME 22 (2011) Andresen O’Gorman Works 1965-85. p. 20 [accessed 13 May 2020] and in Brit Andresen projects, OZ.E.TECTURE, Architecture Foundation Australia [accessed 20 May 2020]. Goad, P. (2011) ‘Timber, Temple, Heaven and Home. The Architecture of Andresen O’Gorman’ UME 22 Andresen O’Gorman Texts and Commentaries. p. 88

[ii] BURRELL COLLECTION COMPETITION: ASSESSORS’ REPORT The Architects’ Journal (Archive : 1929-2005); Mar 22, 1972; 155,12 p. 593

[iii] ‘Andresen Gasson Meunier, Burrell Museum’ (1970-72) (2011). UME 22 Andresen O’Gorman Works 1965-85. P.16 1983-2001. See also Baxter, N. and Sinclair, F. (2016) Scotstyle. 100 Years of Scottish Architecture (1916-2015) Glasgow: The Royal Incorporation of Architects in Scotland. ‘1983. The Burrell Collection, Pollok Park, Glasgow’ Photographs, essay by Ranald MacInnes. pp. 154-155

[iv] St John Wilson, C. (1992) Architectural Reflections. Studies in the philosophy and practice of architecture Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd. p. 18. This book consolidates Wilson’s position as a practising architect and scholar over three decades drawing on the work of Adrian Stokes, Melanie Klein and others.

[v] St John Wilson, C. (1992) p. 3. quotation from Le Corbusier, Vers une Architecture, 1923/ Towards a New Architecture, 1946

[vi] Andresen, B., O’Gorman, P. (2011) ‘Architecture Interacting’ UME 22 Andresen O’Gorman Texts and Commentaries. with reference to the work of Australian painter, William Robinson. p13

[vii] Andresen, B., O’Gorman, P. (2011) ‘Architectural Intention’ UME 22 Andresen O’Gorman Texts and Commentaries p. 11.

[viii] John McAslan & Partners is architect and landscape designer for the restoration and modernisation of the Grade A listed Burrell Collection, currently on-site. John Meunier voiced concerns in 2017 around the redevelopment project’s affect on the graduation of spaces.

Photography Lindsay Johnston

Drawings Helmut Jacoby

Suzanne Ewing is an architect and educator, Professor of Architectural Criticism at The University of Edinburgh. She is co-founder of Zone Architects, editor of academic journal Architecture and Culture, and co-leads Voices of Experience, a project/network uncovering and disseminating the contribution of women to the built environment in Scotland.