Two years ago when The Burrell Collection was closed for renovation, Suzanne Ewing wrote in DES about her deep affection for the building & its collection. Now reopen, she revisits & re-acquaints with the space, the light & the collection.

Sylvan space

Around 11am daylight skims the musty alabaster folds on St Anthony of Egypt’s hood (carved c. 1450). When I return an hour later, it is illuminating the sideways glance of Rodin’s bronze Jean d’Auré (cast 1895), a man who was taken hostage to save citizens when his hometown of Calais was under siege. By one o’clock the stoneware Luohan Buddha (Ming dynasty), in deep meditation and also with his back to the woodland, is caught in the sun-shaft. A few conservators are focused on final dustings, tweaking display cases and testing interactive screens before the building opens to the public in a day’s time. [1] One of the delights of visiting this museum has always been its combination of enduring invitation and new discoveries: feeling free to veer off paths, to linger in a warm or shady spot.

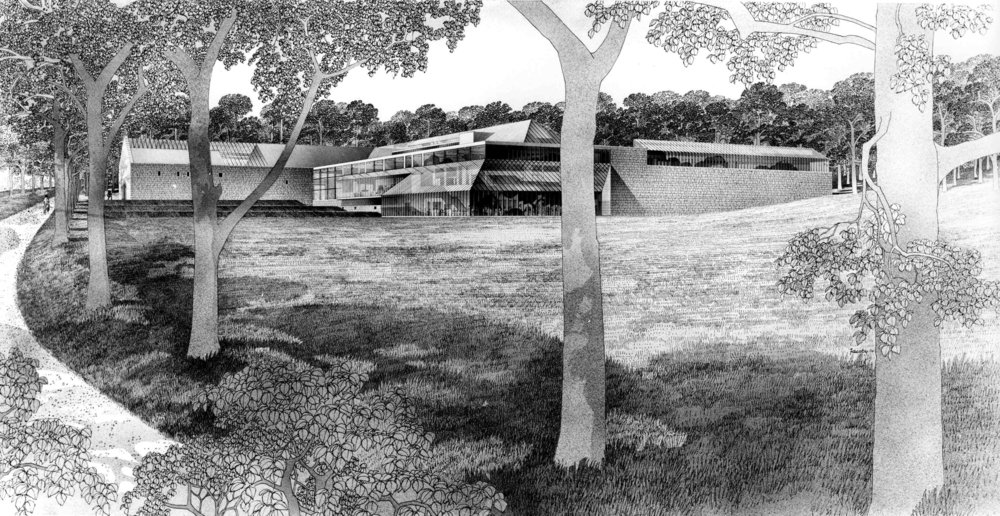

The restored northern galleries are a reassuring return to the meandering encounters of the originally envisioned ‘walk in the woods’. A designed place which shelters these figures and other objects dislocated from their sites and cultures of origin. Renewed Jurassic Portland stone of the plinths and the floor is offset with a light putty-coloured wall finish. This concrete columns, galvanised steel flanges supporting the warm, still majestic timber structure, frame the lighter mullion rhythm of the performance-enhanced long glazed wall. However it is the counterpoint of the shadowy elevated route through the new mezzanine galleries that really enhances the promise of landscape immersion, the sylvan environment conveyed in Helmut Jacoby’s competition drawings [2].

“. . illuminated by natural light, the artefacts are poised on the threshold with the natural world, the visitor too; mind and body are exposed to the artworks and their architectural setting; unguarded and vulnerable; and as a result we are more receptive to each artefact.” [3]

Clusters of exquisite ceramics, lace, beads, carved timber are now presented in purpose designed cases with exquisite stainless steel rod lights. In the intimate, semi-enclosed areas on the upper level, tightly calibrated illumination dances with faint woodland reflections on the surface of vitrines. There is a consistent draw to the lighter perimeter and columnar structure beyond, demonstrating an ‘intricacy’ which one of the original architects, John Meunier, has explored [4]. The mezzanine galleries traverse the length of the building from the red sandstone courtyard to a veiled view over the park at the east end. Top-lit crossings punctuate the route between the rooms. Being closer to the tectonic pitch of the roof structure increases awareness of the extent and profile of the glazed exterior skin and the chequerboard oak floor.

Servicing the collection: re-placings

John Rattenbury, the Burrell Collection’s Guide Organiser, described the building after its closure on 23 October 2016 as ‘empty and lonely’ [5]. The 9000 objects in the collection have determined the design brief for the ‘new’ Burrell as much as expectations of contemporary museum experience and necessary upgrading of the built fabric. The highly choreographed six-month period of collection removal, followed by a designed strip-out of the Category A listed building is more akin to the servicing a well-loved vintage car than the usual logics of building construction. Packings, unpackings, inventories, specialist research and interpretation work over the past five years have informed detailed display design and museum layout, as well as constructional intervention and environmental modelling and decisions.

The design brief was to increase what is on show and to ensure that the majority of the collection is now stored on site. The response has involved a range of displacement strategies, conservation-led design criteria and spatial reconfiguration of the lower levels. Bespoke protective techniques were developed for artefacts built into the fabric, such as The Warwick Vase (Hadrian’s Villa then Warwick Castle from 1770s) and the Bridgewater ceiling (medieval origins, Somerset until 1890) which constrained any repositioning. The internally planted fig trees have not been replaced as their potential harbouring of insect life puts delicate textiles at risk. Smoothing out access roads in Pollok Country Park was needed not only for construction and building utility access but for insurance requirements to safely move objects four miles southwest to and from Glasgow Museums Resource Centre.

Servicing the building: towards a more nuanced environment

There is a visceral sense of the ‘original’ in instances such as the still rubbed-worn parapet ledges, noticeable now that they are adjacent to freshened paint, precisely inserted digital or glazed screens and environmental monitoring sensors. The well loved 1958 Børge Mogensen cognac leather chairs are once again installed against the sandstone courtyard walls, leaning together like a group of old friends. 1980s ventilation grilles have a dull rather than shiny tone. The external joinery screens of the educational rooms above the old entrance have a comforting varnished patina protected by the enveloping pitched canopy of the fully replaced glass and aluminium façade and roofing.

The architects, John McAslan + Partners, describe their design approach to the project as ‘fabric first’ [6]. There is a significant volume of glass and aluminium recycling, with the external skin replaced with high-spec glass modulated to the building’s differing elevations, led by Arup façade engineers [7]. Reconfiguration of the roof profile to avoid the poolings of water and leaks from flat roof areas has offered opportunity to add photovoltaic arrays. The majority of material decisions continue the limited palette of the 1983 construction and spatial flow, with the exception of the ‘hub’ replacing the lecture theatre.However, it is the internal environmental design and performance that is one of the most sophisticated aspects of this design reconditioning. The apparently minimal alteration to much of the Burrell’s spaces has only been by achieved through a complete overhaul of the energy systems, plant and environmental technology, woven into the original structured labyrinth of servicing ducts built into existing walls and floors. Environmental engineer, David Cameron from Atelier Ten [8] notes how the shadow of the 1970s energy crisis informed the decision for the building’s fully electric state-of-the art plant ‘engine’ and an organising ethos of thermal mass and gain.

Challenges included working with these logics within a predominantly greenhouse envelope to both north and south orientations, alongside significant air leakage in the in-built mechanical distribution vents. With the original electric boilers removed, a much smaller but more sophisticated system of zoned heating and air handling systems has been installed in the underbelly of the building, augmented with a new gas supply to offer potentially diverse future energy options. Detailed thermal and daylight modelling led to performance specifications for glass installation. 22 new environmental zones are serviced by re-lined under-floor and in-wall ducts which has reduced air leakage, ultimately achieving a consistent internal temperature of around 21 degrees Celsius and stable air change rate throughout the public areas.

In contrast with the landscape horizons of the northern and mezzanine galleries, the spatial flow from the new entrance through the half-hollowed Hutton rooms to the ‘hub’ has a more internalised raumplan quality. The glazed south facing entrance and positioning of internal walls with glass screens on the new mezzanine is informed by environmental modelling, utilising waste heat from the plant below, ensuring the volume and external skin combine to maximise energy efficiency. For the past 10 months, environmental sensors have been feeding data into ongoing modelling of seasonal and occupational conditions, which will continue for the first three years of re-opening. In surprisingly warm March sun, the stained glass walk and corner café air felt almost crisp, far from memories of the persistent beating sun when previously queuing for a coffee.

Serving/servicing the city?

A condition of the Burrells’ gift to Glasgow was a detachment from the urban. The sylvan spaces now shelter interpretation displays which hint at the earlier travels and trials of this eclectic, abundant gift to the city almost ninety years ago. The museum now offers glimpses of Provand’s Lordship, Kelvingrove Art Gallery, Mavisbank Quay, the vessels and outlets of nineteenth century art market traders and Sir William and Lady Constance Burrell’s homes in the west end of Glasgow and Northumberland. The extent and complexity of labour, wealth and family relations intertwined with these artefacts and their housing is an ongoing story of the politics of giving and receiving.

In many ways the ‘new’ Burrell is an exercise in conserving a much loved experience, achieved through significant displacements and adjustments of both objects and the building fabric and its systems, design as reconditioning. Success of the £68million spent on sustaining this civic gift will be measured through remembered familiarity but also the quality of respite from the contemporary city. The new external landscape, which already seems cluttered, has been necessary for the mobility of the collection and pedestrians, for access and new service infrastructure, though it feels similar in specification to current town centre improvements. There is an ease, with moments of ‘intricacy’, to the internal spatial flows that extend the original and override the initial impact of the underwhelming entrance screen. The new ‘hub’, while the most significant constructional intervention, is the least defined as an internal destination, but is the main locus of digital interpretation.

Gifts are always conditioned by the time and place of their receipt. In the Burrell’s case, the 1944 Collection was given to a wartime, ravaged city; in 1953 the gift of Pollok Park was distanced from post-war city development; the 1972-1983 architectural competition fixed the collection in place and re-set Glasgow’s cultural orientation and reputation; the 2020s reconditioning navigates globalised configurations and questions of information, provenance and privilege, perhaps more open to how pieces of the collection may move again.

1 With thanks to Gordon Boag (Glasgow Life) and Susanna Beaumont (Design Exhibition Scotland) for facilitating a pre-opening visit on 28 March 2022

2 Suzanne Ewing, ‘A Walk in the Woods; shelter in place’, Design Exhibition Scotland 2020.

3 John Meunier, Patrick Lynch (editor), Simon Henley and David Grandorge On Intricacy: The Work of John Meunier Architect, Canalside Press, 2018. [https://www.canalsidepress.com/intricacy-work-john-meunier-architect/ Accessed 03.04.2022] p.140.

4 Meunier et al. 2018. p.105 is a photograph of the interior of the northern galleries viewed through the external glass skin reflecting the surrounding tree foliage.

5 John Rattenbury, ‘The Burrell Collection Restoration’, Architectural Heritage Society of Scotland lecture, The Renfield Centre, Glasgow, and online, 24 March 2022

6 https://www.mcaslan.co.uk/work/burrell-collection

7 https://www.arup.com/projects/burrell-collection

8 Tour from a building service design perspective kindly offered by David Cameron of Atelier Ten on 28 March 2022 https://www.atelierten.com/projects/the-burrell-renaissance/

The Burrell Collection is open Monday-Thursday and Saturday 10am-5pm; Friday and Sunday 11am-5pm.